home ::

syllabus ::

timetable ::

groups ::

moodle ::

video ::

© 2021

- "Don’t worry if it doesn’t work right. If everything did, you’d be out of a job."

- Mosher’s Law of Software Engineering

- "One (person)’s crappy software is another man’s full time job."

- Jessica Gaston

Testing bingo: do you know these terms?

- Definitions

- V-diagram, requirements (are a dirty word?),

- unit test, systems test, integration test, acceptance test (alpha, beta), contractual and regulatory

- state space

- Goals: functional (e.g. Performance), non-functional (e.g. the "ilities... can you name three?)

- Testing is East: Test-driven development

- is a useful process (for small teams)

- gets very complex for large teams

- is not a quality assurance activity

- red, green, refactor

- Testing is hard

- Infinitely good tests are infinitely expensive

Later:

- Types of testing

- black box (aka functional), all-pairs, metamorphic testing, fuzzing (dumb, generational, mutation, coverage)

- white box, formal testing

- Coverage criteria: path, state, transition, function, statement, du, branch

- Test case prioritization

- O'nite regression tests

- Triage

- O'nite regression tests

- Software works (usually). Why? How can we exploit that?

- f u cn rd ths, u cn gt a gd jb n sftwr tstng.

- Anonymous

- "Program testing can be a very effective way to show the presence of bugs, but is hopelessly inadequate for showing their absence."

- Edsger Dijkstra

- If debugging is the process of removing bugs, then programming must be the process of putting them in.

- Edsger Dijkstra

- Beware of bugs in the above code; I have only proved it correct, not tried it.

- Donald Knuth

- ... it is a fundamental principle of testing that you must know in advance the answer

each test case is supposed to produce. If you don't, you are not testing; you are experimenting."

- Kernighan and Plauger

- Debugging is like a mystery novel where you are both the

detective and the murderer.

- Anon

Testing had to be discovered:

- It was on one of my journeys between the EDSAC room and the

punching equipment that ‘hesitating at the angles of stairs the

realization came over me with full force that a good part of the

remainder of my life was going to be spent in finding errors in

my own programs.

- Maurice Wilkes 1951

First bug

Testing is most of our effort:

- V-diagram

- "Without requirements or design, programming is the art of adding bugs to an empty text file."

-- Louis Srygley - Brooks, Mythical Man Month.

Effort is

- 1/3 th planning

- 1/6 th coding

- 1/4 th unit testing

- 1/4 th systems testing

- "Without requirements or design, programming is the art of adding bugs to an empty text file."

- Unit tests: testing your code

- Systems test: testing how your code works with everyone else's (harder)

- Integration testing: verify the interfaces between components against a software design.

- Acceptance testing:

- User acceptance testing

- Contractual and regulatory acceptance testing

- Alpha and beta testing

- Alpha testing is simulated or actual operational testing by potential users/customer

- Follows alpha testing: external testing with a larger audience

- Released to a limited audience outside of the programming team

- State space: options inside a project

- 300 boolean options = 2300 states

- Given numeric models, search space is infinite

- Inside our software is more states than stars in the sky (1021)

- 300 boolean options = 2300 states

-

Documentation :

- Incomplete, always

- Even if we try to make it complete,complete for who

- Stakeholders, competing goals

- Toronto CS department. Information system

- "good" if parents can track their children

- "good" if students can maintain their privacy

-

For "maintainability?"

- how to test that, except to watch the code for years to come?

-

Performance:

- Energy usage

- Network request response time?

- Minimize variance in query spike time

-

For "usability"?

- For other "ilities" (Maintainability, Customizanility, Scalability, Capacity, Availability, Reliability, Recoverability, Maintainability, Serviceability, Security, Regulatory, Manageability, Environmental, Data Integrity, Usability, Interoperability

Have lots of unit tests!

Run them, a lot!

Get them all passing before checking back to main!

Do not make them into a religion!

Tests suites that run every time you save code

-

Build tests first

-

Repeat:

- Red = fund a broken test

- Green= fix the test

- Refactor= sometimes, clean things up

- Refactoring means functionality stays the same but the resulting code is simpler.

-

Tips:

- rerun "python3 mycode.py" or some pytest equalizing

- keep the tests short (or else)

Test suites that you commit code.

.travis.yml.github/workflows/unittest.yml- keep the tests short (perhaps, not so short)

Kent Beck, 2003:

- No studies have categorically demonstrated the difference between TDD and any of the many alternatives in quality, productivity, or fun. However, the anecdotal evidence is overwhelming, and the secondary effects are unmistakable

David Hansson, 2013:

- Lots of developers that push TDD make you feel like your code is dirty if you are not using TDD.

- Driving your design from unit tests is not a good idea.

- The TDD notion of “tests must be fast” is shortsighted.

- The faith in TDD can lead to completely forgetting about system testing.

- The focus on the unit and the unit only does not help with producing a great system.

- 100% coverage is silly

Karac + Turhan (2018): TDD can't really be defined or shown to be effective

-

What Do We (Really) Know about Test-Driven Development?

- Itir Karac and Burak Turhan

-

TDD has too many cogs,

-

Its effectiveness is highly influenced by the context (for example, the tasks at hand or skills of individuals),

-

The cogs highly interact with each other

- e.g. Insufficient TDD experience of knowledge

- e.g. Insufficient design

- e.g. Insufficient developer testing kills,

- e.g. Domain and tool specific limitations

- e.g. Precedence of legacy code

- e.g. Insufficient adherence to TDD testing protocol,

- TDD isn’t a dichotomy in which you either religiously

- write tests first every time

- or always test after the fact.

- TDD is a continuous spectrum between these extremes,

- Developers tend to dynamically span this spectrum, adjusting the TDD process as needed

- Studies of 416 developers over more than 24,000 hours

- only 12 percent of the projects that claimed to use it, actually did "write test first"

- Studies of all Java projects in Github

- applied heuristics for identifying TDD-like repositories

- Only 0.8 % were TDD. And in that set, no evidence for

- no evidence for higher commit velocity

- no evidence for more issues reported or retired

- TDD isn’t a dichotomy in which you either religiously

- Does TDD only perform better when compared to a coarse-grained

rigid old-fashioned development waterfall process?

- TDD’s superiority over a test-last approach were due to the fact that most of the experiments employed a coarse-grained test-last process closer to the waterfall approach as a control group

- Testing to check that the promised behavior actually works?

- But the documentation is incomplete, always

- Even if we try to make it complete, complete for who?

- e.g. Stakeholders, competing goals

- Toronto CS department. Information stem

- "good" if parents can track their children

- "good" if students can maintain their privacy

- How to write tests?

- Are any of the following mutually exclusive?

- For "maintainability?"

- how to test that, except to watch the code for years to come?

- Research task: can we learn from prior maintainability?

- Performance:

- Energy usage

- Network request response time?

- Minimize variance in query times

- etc etc

- For "usability"? Did you do that in HW3?

- For other "ilities" (maintainability, customizability, scalability, capacity, availability, reliability, recoverability, maintainability, serviceability, security, regulatory, manageability, environmental, data integrity, interoperability fairness)

- For "maintainability?"

Consider test some web-based app

- Everything that happens to it depends on events, elsewhere on the web

- Those events happen at probability p

- So they don't happen at probability (1-p)

- So they don't happen after n tests at probability (1-p)n

- So they do happen after n tests at probability C(p,n) = 1- (1-p)n

- That's a lot of tests

Problems:

- Infinite testing is infinitely expensive

- rearranging

C(p,n) = 1- (1-p)n

we get

n = log(1-C) / log(1-p) - For certainty (C=1) for low probability events (small p=0) then n explodes.

- rearranging

C(p,n) = 1- (1-p)n

we get

- Real world events hard to model with certainty

- Events happen at probability p?

- What p?

Also, what about rare events?

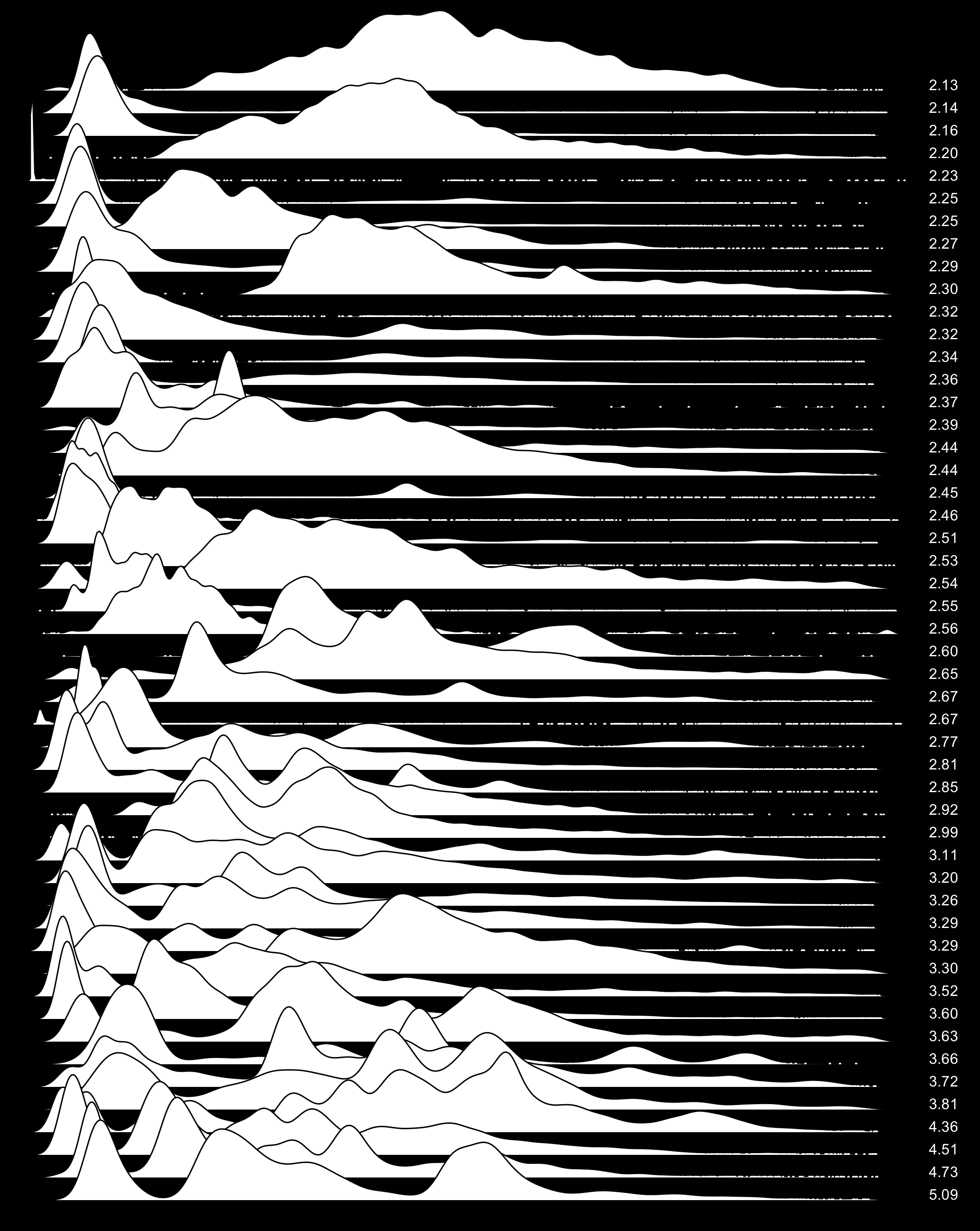

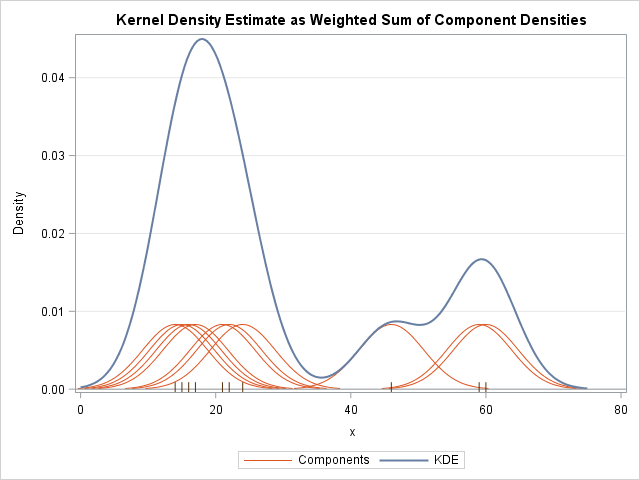

Can apply some non-simple stats to model arbitrary distributions as combinations of (e.g.) Gaussian kernels (think wavlets or Fourier series, if you know that stuff).

Or, for really weird functions, use non-parametric methods that divide the data into chunks, then reasons separately about each chunk:

- Also known as functional testing

- Can't look inside the code

- e.g. Reflect on input space to find interesting regions

- e..g Look for clusters in the input or output space

- e..g if age runs 0...120

- try less-than-min, in-range, more-than-max

- e.g. 1, 60, 150

- e.g. all pairs testing

- Let the inputs be a vector showing choices per input

- Find inouts that never use the same pair of values, twice.

- e.g. three binary inputs, one "days of week"

and something with a range of 10 inputs

- e.g. (happy:boolean rich:boolean healthy:boolean restDay:dayOfWeek exercise:1..10))

- ranges: (2 2 2 7 10)

- so fi wever you use happy=true and restDay=sunday then you can never test that pair again

- e.g. (t * * sunday *) can only appear once

- when processed by an

all-pairs

generator

(ipo '(2 2 2 7 10))(see below) - BTW, all pairs is an amazing heuristic for exploring a large space

- Let the inputs be a vector showing choices per input

- e..g if age runs 0...120

((2 2 1 1 1) ; e.g. (true true true and first value of rest)

(2 1 2 2 2) (1 2 2 3 3) (1 1 1 4 4)

(2 2 2 7 5) (2 2 2 6 6) (2 2 2 5 7)

(2 2 2 4 8) (1 1 2 1 9) (1 1 1 7 10)

(1 1 1 6 5) (1 1 1 5 6) (2 1 1 3 3)

(1 2 1 2 2) (2 2 1 7 9) (1 1 1 7 8)

(1 1 1 7 7) (0 0 0 7 6) ; note "0" means "don't care"

(2 2 2 7 4) (0 0 0 7 3) (0 0 0 7 2)

(1 1 2 7 1) (2 2 2 6 10) (0 0 0 6 9)

(0 0 0 6 8) (0 0 0 6 7) (0 0 0 6 4)

(0 0 0 6 3) (0 0 0 6 2) (0 0 0 6 1)

(0 0 0 5 10) (0 0 0 5 9) (0 0 0 5 8)

(0 0 0 5 5) (0 0 0 5 4) (0 0 0 5 3)

(0 0 0 5 2) (0 0 0 5 1) (0 0 0 4 10)

(0 0 0 4 9) (0 0 0 4 7) (0 0 0 4 6)

(0 0 0 4 5) (0 0 0 4 3) (0 0 0 4 2)

(0 0 0 4 1) (0 0 0 3 10) (0 0 0 3 9)

(0 0 0 3 8) (0 0 0 3 7) (0 0 0 3 6)

(0 0 0 3 5) (0 0 0 3 4) (0 0 0 3 2)

(0 0 0 3 1) (0 0 0 2 10) (0 0 0 2 9)

(0 0 0 2 8) (0 0 0 2 7) (0 0 0 2 6)

(0 0 0 2 5) (0 0 0 2 4) (0 0 0 2 3)

(0 0 0 2 1) (0 0 0 1 10) (0 0 0 1 8)

(0 0 0 1 7) (0 0 0 1 6) (0 0 0 1 5)

(0 0 0 1 4) (0 0 0 1 3) (0 0 0 1 2))- One trick in black box testing

- Read the doc

- Doodle a model showing expectations

- Generate tests over that doodle

- Coverage criteria (for finite-state machines)

- Test coverage: cover every path: no feasible due to infinite number of paths (cycles)

- State coverage: every node coverage (minimal testing criterion)

- Transition coverage: every edge covered

- E.g. here are five tests covering every edge

- Is this still "just" functional testing.

Dumb Fuzzing :

- Fuzz testing was originally developed by Barton Miller at the University of Wisconsin in 1989.

- throw random cr*p at a program till it crashed

- brute force mutation

- History:

-

1981: Duran and Ntafos investigated the effectiveness of testing a program with random inputs.

- Previously: random testing had widely perceived to be worst means of testing

- Their analysis: random proves are a cost-effective alternative to more systematic testing

-

1983: Steve Capps developed "The Monkey", a tool that would generate random inputs for classic Mac OS applications, such as MacPaint.

- The figurative "monkey" refers to the infinite monkey theorem which states that a monkey hitting keys at random on a typewriter keyboard for an infinite amount of time will eventually type out the entire works of Shakespeare. In the case of testing, the monkey would write the particular sequence of inputs that will trigger a crash.

-

1988: Barton Miller: when he was logged to a modem during a storm, there was a lot of line noise generating junk characters and those characters caused programs to crash

- New term: _fuzzing = automatically generate random files and command-line parameters for the utility.

- The project was designed to test the reliability of Unix programs by executing a large number of random inputs in quick succession until they crashed.

-

Recently, numerous examples where fuzzing found bugs other approaches missed

-

- Simple fuzzing: advantages:

- Very cheap to generate a test

- Exploit CPUs to explore a broad range of options

- Useful for dodging incorrect preconceptions of what the program should do

- Good for detecting events that lead to buffer overflow, DOS (denial of service), cross-site scripting and SQL injection

- Simple fuzzing: disadvantages:

- It cannot provide a complete picture of the overall security, quality or effectiveness of a program

- Spends much time generating impossible inputs or very unlikely events

Smarter fuzzing:

- Express input as a grammar

- Generate from tree

- Generational fuzzing

US_PHONE_GRAMMAR = {

"<start>": ["<phone-number>"],

"<phone-number>": ["(<area>)<exchange>-<line>"],

"<area>": ["<lead-digit><digit><digit>"],

"<exchange>": ["<lead-digit><digit><digit>"],

"<line>": ["<digit><digit><digit><digit>"],

"<lead-digit>": ["2", "3", "4", "5", "6", "7", "8", "9"],

"<digit>": ["0", "1", "2", "3", "4", "5", "6", "7", "8", "9"]

}- Example

[simple_grammar_fuzzer(US_PHONE_GRAMMAR) for i in range(5)]

['(692)449-5179',

'(519)230-7422',

'(613)761-0853',

'(979)881-3858',

'(810)914-5475']

Mutational fuzzing:

- Take a known valid input

- Mutate it

def mutate(s):

"""Return s with a random mutation applied"""

mutators = [

delete_random_character,

insert_random_character,

flip_random_character

]

mutator = random.choice(mutators)

# print(mutator)

return mutator(s)

for i in range(10):

print(repr(mutate("A quick brown fox")))

'A qzuick brown fox'

' quick brown fox'

'A quick Brown fox'

'A qMuick brown fox'

'A qu_ick brown fox'

'A quick bXrown fox'

'A quick brown fx'

'A quick!brown fox'

'A! quick brown fox'

'A quick brownfox'Coverage fuzzing

- Track parts of the grammar seen so far

- Fuzz to some new place.

Mining examples to weight crammers:

- Take a library of good examples

- Weight sub-trees on (e.g.) Probability

- Stochastic recursive descent:

- Stochastically select sub-trees according to their weights

- If weight = random then generational fuzzing

- If select to prefer min weights, then coverage fuzzing

- Recurs into sub tree.

- Stochastically select sub-trees according to their weights

Smarter smarter fuzzing = genetic programming

- We we dynamically adjust weights to prefer certain goals

- then "testing" becomes AI

- then "testing" becomes "mitigation" or "optimization"

How to test with an oracle for the specifics of the domain?

Metamorphic relations (MRs) are necessary properties of the intended functionality of the software

-

high-level statements that should be true across all inputs

-

e.g. conjunctions do not lead to more output

- RESULT1= "all males"

- RESULT2="bald males"

- RESULT2 should not be larger than RESULT1

-

e.g. When testing a booking website, a web search for RESULT1= accommodation in Sydney, Australia, returns 1,671 results

- RESULT2= Filter the price range or star rating and apply the search again;

- RESULT2 should be a subset of RESULT1

A wonderful metamorphic testing result: Z. Q. Zhou, T. H. Tse and M. Witheridge, Metamorphic Robustness Testing: Exposing Hidden Defects in Citation Statistics and Journal Impact Factors in IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, doi: 10.1109/TSE.2019.2915065.

White box: we can open up the code and look inside:

- Coverage criteria (for code)

- Functions (all functions called once);

- A very weak test

- Statement coverage

- Supported by many tools

- du coverage:

- find all paths between where a variable is defined and used.

- Branch coverage:

- has every condition in the program be explored;

- Functions (all functions called once);

- Warning: you can succeed on all the above, and the code still crashes.

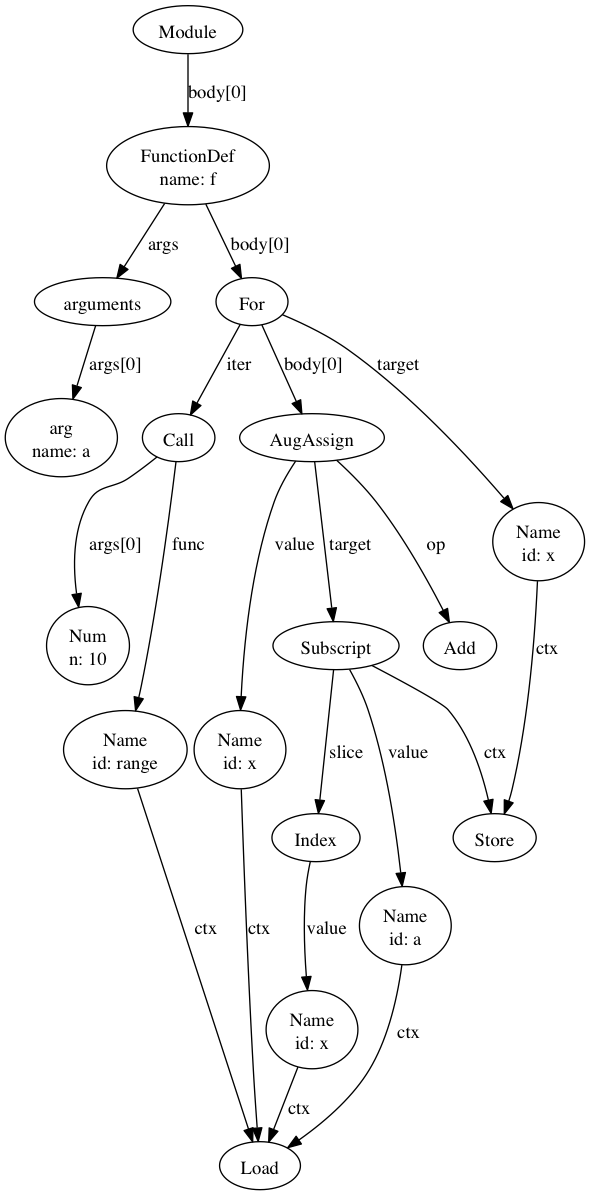

Symbolic execution:

- Find the abstract syntax tree of the code

- e.g. python3's

ctreepackage

- e.g. python3's

import ctree

def f(a):

for x in range(10):

a[x] += x

tree1 = ctree.get_ast(f)

ctree.ipython_show_ast(tree1)Applications of symbolic execution:

- Walk the tree to collect the constraints to build the tests.

- Can lead to spectacular reductions to black box testing

- e.g. BigTest: White-Box Testing of Big Data Analytics [ESEC/FSE 2019]

- Scripts processing gigabytes of data sets

- Is this a hard testing problem?

- Q: Do the tests have to handle all the possible combinations in the data?

- A: No: they only need to cover all the branches of the code

Express english requirements as checkable logic, then use logic to reason about it

Other examples:

-

Product lines:

-

Temporal logic (add operators for until ("U") and always "[]" eventually "<>"

- always ∀, there exists at least one ∃

- e.g. elevator door stays open between X and Y

(From One-Click Formal Methods:

- FORMAL METHODS: mathematically based approaches for specifying, building, and reasoning about software.

- Despite 50 years of research and development, formal methods have had only limited impact in industry.

- Some in such domains as microprocessor design and aerospace.

Why not widely used?

- The modeling cost: Analysts must create a systems model (what is the system) and a properties model (what is meant to do). Properties model usually much smaller than systems model.

- The execution cost: Rigorous analysis of formal properties needs a full search of systems model.

- The personnel cost: Analysts skilled in formal methods must be recruited or trained. Such analysts are generally hard to find and retain.

- The development brake: The above costs can be so high that the requirements must be frozen for some time while we perform the formal analysis. Hence, one of the costs of formal analysis is that it can slow the process of requirements evolution.

Recent experience at Amazon:

- More and more, web-based systems are configured in sufficient detail

- Such that processes can be bounced around from node to node on the cloud (to make best use of spare resources)

- Application program interfaces (APIs) of cloud services are computer-readable contracts that establish and govern how the system behaves.

- Most importantly, since those models are utilized by a large user community,

- now economically feasible to build the tools needed to verify them

- Most importantly, since those models are utilized by a large user community,

- Which means that we have enough information to auto-configure our formal methods

- and the size of the potential user community and the business value now justifies the cost of formal methods.

A feature model is a "product line"; i.e. a description of a space of products.

Question: what are the different products we can pull from the following?

Now that was a small feature model. Suppose we are talking about something really big like a formal model of the LINUX kernel with 4000 variables and 300,000 contrast. Q: How to reason over that space? A: use a theorem prover. e.g. Pycosat.

The following example comes from the excellent documentation at the Python Picostat Github page

Let us consider the following clauses, represented using

the DIMACS cnf <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conjunctive_normal_form>_

format::

p cnf 5 3

1 -5 4 0

-1 5 3 4 0

-3 -4 0

Here, we have 5 variables and 3 clauses, the first clause being

x1 or not x5 or x4

Note that the variable x2` is not used in any of the clauses, which means that for each solution with x2 = True, we must also have a solution with x2 = False. In Python, each clause is most conveniently represented as a list of integers. Naturally, it makes sense to represent each solution also as a list of integers, where the sign corresponds to the Boolean value (+ for True and - for False) and the absolute value corresponds to i-th variable::

>>> import pycosat

>>> cnf = [[1, -5, 4], [-1, 5, 3, 4], [-3, -4]]

>>> pycosat.solve(cnf)

[1, -2, -3, -4, 5]

This solution translates to: x1=x5=True, x2=x3=x4=False

To find all solutions, use itersolve::

>>> for sol in pycosat.itersolve(cnf):

... print sol

...

[1, -2, -3, -4, 5]

[1, -2, -3, 4, -5]

[1, -2, -3, 4, 5]

...

>>> len(list(pycosat.itersolve(cnf)))

18

In this example, there are a total of 18 possible solutions, which had to be an even number because x2 was left unspecified in the clauses.

The fact that itersolve returns an iterator, makes it very elegant

and efficient for many types of operations. For example, using

the itertools module from the standard library, here is how one

would construct a list of (up to) 3 solutions::

>>> import itertools

>>> list(itertools.islice(pycosat.itersolve(cnf), 3))

[[1, -2, -3, -4, 5],

[1, -2, -3, 4, -5],

[1, -2, -3, 4, 5]]

Feature Models and Product Lines: Software installation as a formal methods problem

Lets represent software dependencies in a logical framework:

If we run Picosat over these formulae then:

- Any solution that satisfies all the constraints...

- Is a different way to create a valid install of the program.

Variants:

- min install:

- add a cost to the install effort of each part

- score everything coming out of

itersolve(sum that cost) - pick the easiest thing to install

- optimizing:

- generate one solution, ask some human what they think

- if they don't like, negate it add it to the theorems

- so future solutions will not contain the thing you don;t like

Important note: in practice, except for trivally small problems, no one writes DIMACS manually.

- Instead, we write code to generate DIMACS via some code.

- For example: running code.

In summary, in theory, it is can be useful to reformulate SE tasks as a SAT task. As Micheal Lowry said at a panel at ASE’15:

- It used to be that reduction to SAT proved a prob- lem’s intractability. But with the new SAT solvers, that reduction now demonstrates practicality."

However, in practice, general SAT solvers, such as the Z3, MathSAT [29], vZ et al., are challenged by the complex- ity of real-world software models. For example, the largest benchmark for SAT Competition 2017 [31] had 58,000 variables– which is far smaller than (e.g.) the 300,000 variable problems seen in the recent SE testing literature [4].

So SAT solvers are great but as software gets really really big, they need help.

- Scalable product line configuration: A straw to break the camel's back Abdel Salam Sayyad, Joseph Ingram, H. Ammar, Tim Menzies 2013 28th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE)

- Building Very Small Test Suites (with Snap), Jianfeng Chen, Xipeng Shen, Tim Menzies, 2020

- Continuous change to the code base

- Continuous testing

- January to October 2013

- Google ran 3 billion unit tests

- Global network of machines

- Problems

- Running out of cpu

- less that 0.5% of those tests ever failed

- Long lags from submission to “passed

- Test case prioritization

- Select test if (a)new, or (b)recently failed or (c) not recently executed

- Found more tests that failed, much earlier

- Greatly reduced time for programmers to get feedback

- Very many prioritization schemes

- Different according to what information they need

- How Different is Test Case Prioritization for Open and Closed Source Projects?, Xiao Ling, Rishabh Agrawal, and Tim Menzies.

Large overnight run of all tests.

- when something crashes, there is no link of crash back to line numbers. Pause. What?

- Turns out, there is no information in that.

- When something crashed, it coes to an off shore team of experts to decide which teams (back in the USA) need to fix the bug).

General lesson:

-

Need to test less

-

TERMINATOR: Better Automated UI Test Case Prioritization, Zhe Yu, Fahmid Fahid, Tim Menzies, Gregg Rothermel, Kyle Patrick, Snehit Cherian, (ESEC/FSE ’19, SEIP), August 26–30, 2019, Tallinn, Estonia.

Q: Why does testing work?

- A: Software runs in a small part of the total space

Marek Druzdzel, diagnosis

- application for monitoring patients in intensive care.

- software had 525,312 possible internal states

- the application reached few of them at run time:

- one of the states occurred 52 percent of the time,

- 49 states appeared 91 percent of the time.

NASA software data: Most faults lie in a small proportion of the files.

- T. Menzies, J. Greenwald and A. Frank, "Data Mining Static Code Attributes to Learn Defect Predictors," in IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 2-13, Jan. 2007, doi: 10.1109/TSE.2007.256941.

AT&T software data: about 80% of the defects come from 20% of the files

- Ostrand et al., “Where the Bugs Are,” Proc. ACM Int’l Symp. Software Testing and Analysis, 2004.

Ditto for the GNU "C" compiler, GCC

- Hamill, Goseva-Popstojanova, Common Trends in Software Fault and Failure Data IEEE TSE, 35(4) 2009

Jospeh Horgan and Aditya Mathur reported in “Software Testing and Reliability” that testing often exhibits a “saturation effect”; i.e. most program paths get exercised early with little further coverage improvement as testing continues.

- see The Handbook of Software Reliability Engineering, 1996).

As to mutation testing, Christopher Michael found that in 80 to 90% of cases, there were no changes in the behavior of a range of programs despite numerous perturbations on data values using a program mutator

- C.C. Michael, ‘On the uniformity of error propagation in software’, Proceedings of the 12th Annual Confererence on Computer Assurance (COMPASS ’97) Gaithersburg, MD, 1997.

So do not poke everything, everywhere

- Rather, poke around, some

- Where anything starts to fail,

- Move in for a closer look

Don't believe me? Well...

- Fuzzing... works

- Metamorphic testing... works

But what about safety critical applications?

- Demand vastly simpler code

- Tested using vastly longer testing cycles

- Test generated via a very thorough requirements process.

For more see:

- The Strangest Thing About Software. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/2961707_The_Strangest_Thing_About_Software

.gif)