by Ksenia Kharitonova

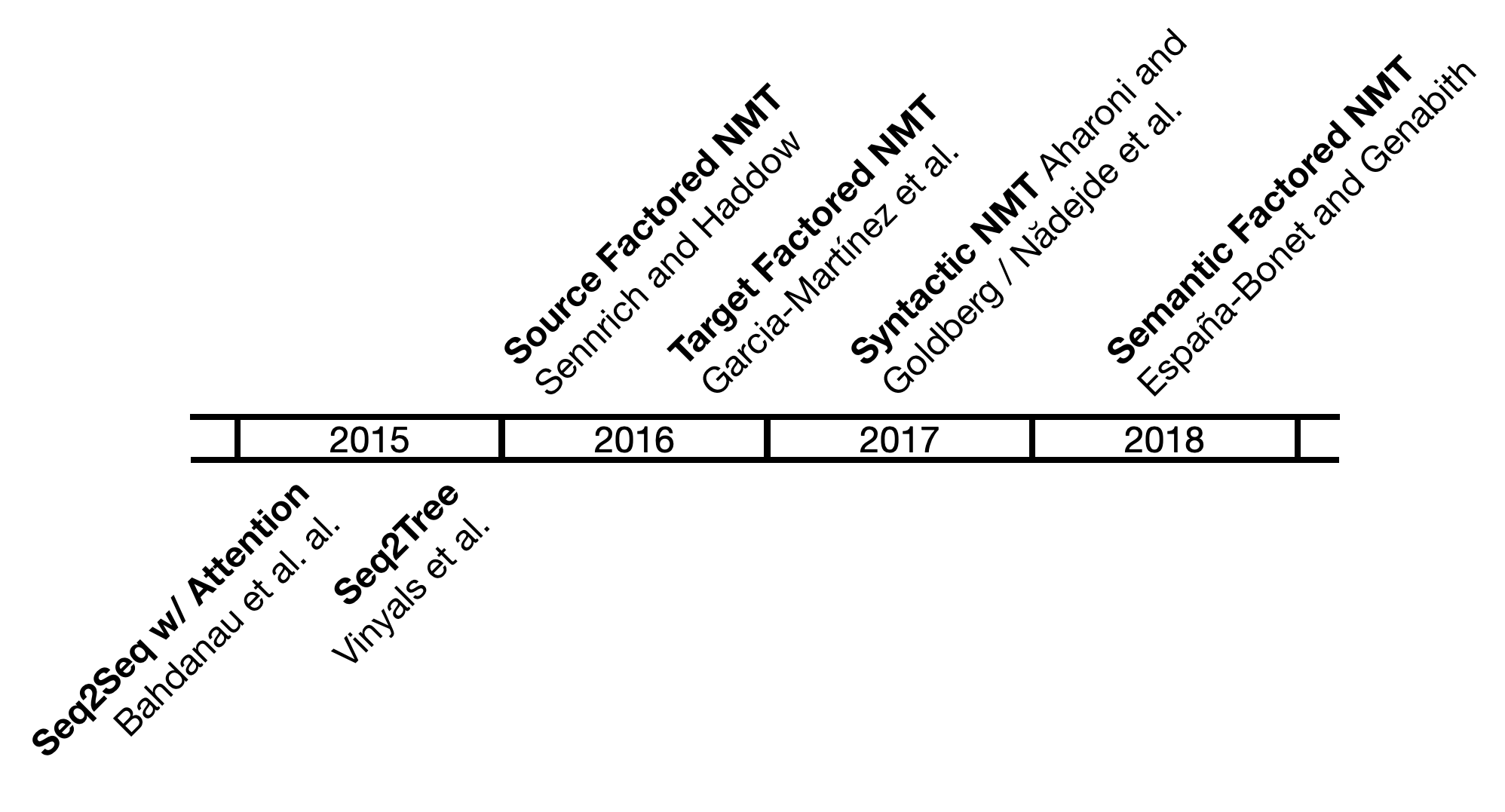

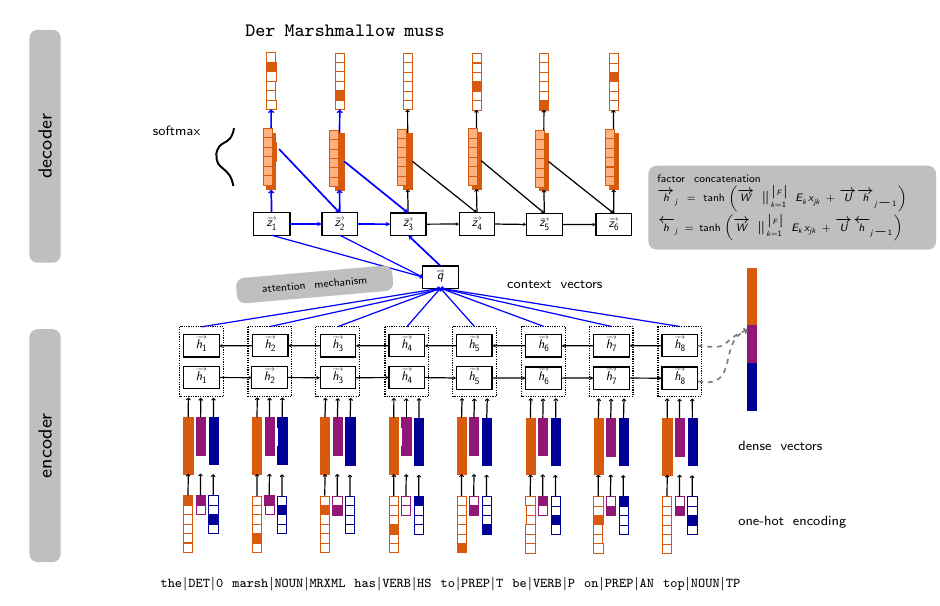

This post continues giving the context of our work, and today we will discuss adding linguistic information to neural machine translation. Among different alternatives, factors have been a key way to add this type of information in the neural approach. Factors describe a word by a tuple that adds various linguistic information, such as lemma, morphological information, POS, dependency labels, etc., to its surface form. Using factors as an input to MT models was already possible when the state-of-the-art methods were still based on statistical MT (Koehn and Hoang, 2007); after the advent of encoder-decoder models for NMT with the seminal Bahdanau et al. (2016) work, it was a logical step to add linguistic information to the new NMT architectures.

The majority of contemporary NMT models learn from the raw sentence-aligned parallel data, but the linguistic data can be a much richer source. The morphological, syntactic, and semantic information implicit in sequences of tokens can be extracted explicitly and added to the models as additional input improving the quality of translation. It is especially beneficial for translating between languages with different syntactic organizations as well as dealing with morphologically rich languages.

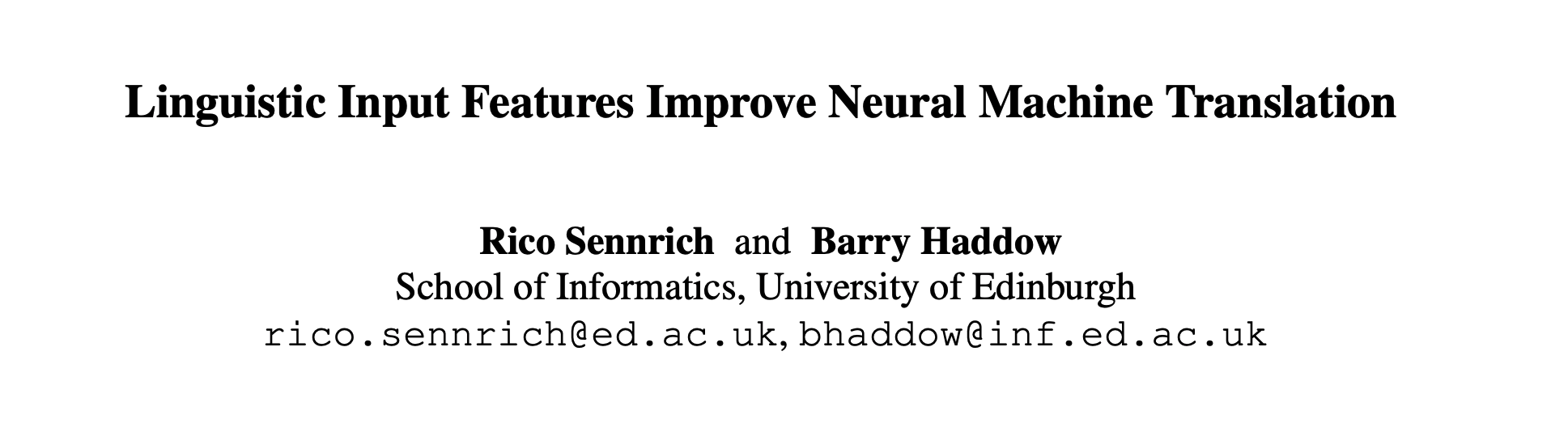

Sennrich and Haddow (2016a) were pioneers in using the additional linguistic information as input for the newly appeared encoder-decoder NMT models. Considering language pairs with less inflective and more inflective languages, such as English and German, they argued that using lemmas beside tokens would reduce the sparsity of the data and allow the inflectional forms of the same word to share the representation in the model. Using parts-of-speech (POS) would help the model disambiguate between the polysemic words where the same word form can share different word types: for example, the English word close could be an adjective, a noun, or a verb, and the architecture that has only tokens as an input was making a mistake of translating this word as the most frequent class (verb) in the sentence.

En: We thought a win like this might be close (ADJ).

*De: *Wir dachten, ein Sieg wie dieser könnte schließen (V).

De: Wir dachten, dass ein solcher Sieg nah (ADJ) sein könnte.

In the cases where the word order in the same phrase in different languages is different,

De: Gefährlich ist die Route aber dennoch . (dangerous is the route but still .)

*En: Dangerous is the route , however .

En: However the route is dangerous .

like in German to English, where the German has a verb-second (V2) word order, whereas English word order is generally SVO, the additional syntactic information of dependency labels could signal to the attentional encoder-decoder to learn which words in the German source to attend (and translate) first.

The proposed architecture of a factored NMT model consisted of a standard sequence-to-sequence RNN encoder - RNN decoder architecture following (Bahdanau et al., 2016), but admitted an arbitrary number of factors (inputs) at the embedding level. Instead of a usual embedding matrix for words at the forward pass, the encoder computed a hidden state with an embedding matrix that concatenated the embedding matrices for all the features along the embedding axis. In order to make the baseline and factored model comparable, the sum of the embedding sizes of the features in the factored model was equal to the word embedding size in the baseline. The model also used a novel subword BPE tokenization of the same authors (Sennrich et al., 2016b) in order to allow for an open vocabulary translation. The linguistic features used in the final model were words (subwords), lemmas, POS, dependency labels, morphological features (for the inflective language, that is, for the German), and the subword tags that for every subword indicated where in the word it belonged.

The evaluation on the English<->German and low-resource English->Romanian translation datasets showed statistically significant improvements in BLEU and perplexity of the model with all the features, and the improvement held for the translation with synthetically enriched data with back-translation. Considering adding one feature at a time, lemmas performed the best on their own. As the examples above show, the most significant improvement could be seen in the specific cases of different word order as well as polysemic words (the incorrect translations were output by the baseline model whereas the factored model produced the correct results).

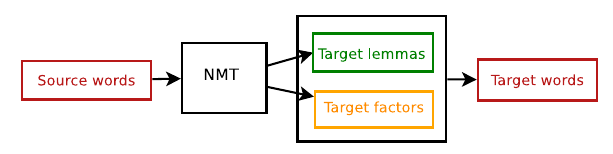

García-Martínez et al. (2016) proposed a different way of incorporating factors in the NMT model. In their case, the factors were not input but predicted: instead of predicting the words themselves, they output the combination of a lemma with a concatenation of the linguistic factors that gave the information on how to inflect a given lemma. For example, from the French word devient, they obtained the lemma devenir and the factors VP3#S, meaning that it is a Verb, in Present, 3rd person, irrelevant gender (#) and Singular. This added a step of generating the final word results by the morphological parser (that was also used to annotate the target words).

The architecture of this model followed (Bahdanau et al., 2016) but the RNN decoder was modified in such a way as to produce two streams of outputs instead of one (the lemmas and the factors). In cases where the decoder produced two sequences of different lengths for lemmas and the factors, the factors sequence was constrained to be the same as the lemmas sequence. In order to be able to use the RNN decoder output for computing the hidden state, different choices for combining the lemmas and factor embeddings were proposed: using only lemmas, combining the two outputs linearly (sum) or non-linearly (tanh).

This model cannot be directly compared to the previous architecture because it did not use the subword segmentation in order to resolve the out-of-vocabulary words problem. In fact, the main improvement of this particular architecture over the contemporary models was exactly that: using lemmas and factors that gave the information of the inflection it reduced the target vocabulary size and produced fewer unknown tokens in the results when translating from a less inflective language (English) to a more morphologically rich language (French). The improvement in translation quality expressed in %BLEU in the original paper was modest.

This approach for resolving the open vocabulary problem was further developed in (Burlot et al., 2017; Garcia-Martinez et al., 2020), where it showed a significant improvement in BLEU on translations from one morphologically rich language (Arabic) to another (French), especially in the case where the subword segmentation (BPE) was also applied.

An adjacent way of incorporating syntactic information in the NMT models makes use not only of the flattened representation of linguistic tags in the form of factor tuples with linguistic information but of the whole linguistic trees based on dependency or constituency grammars.

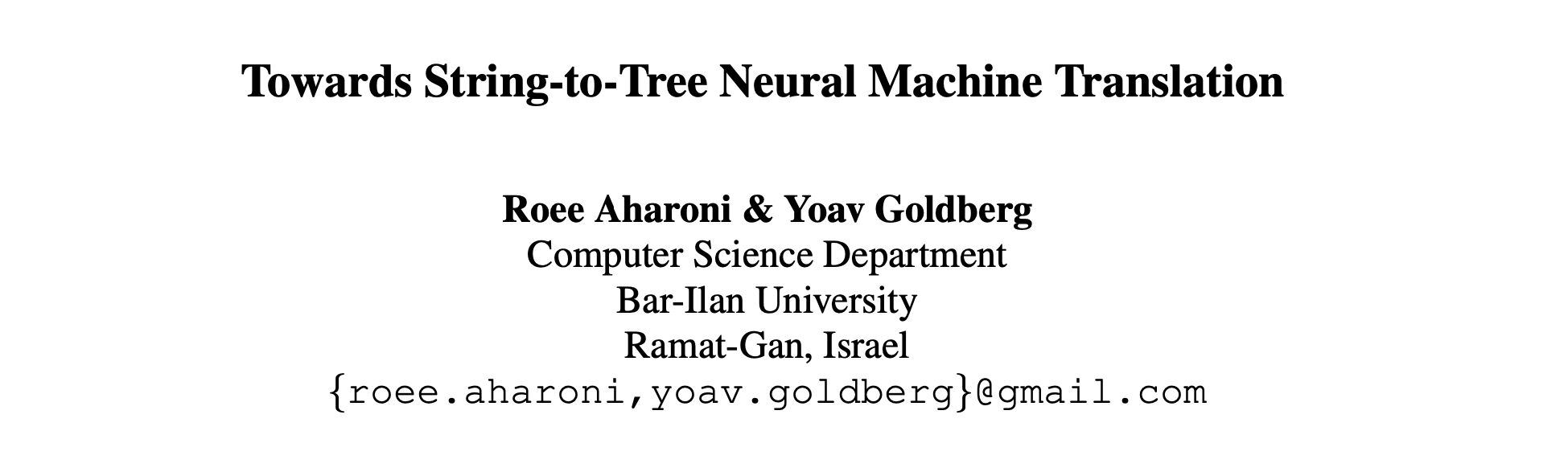

Aharoni and Goldberg (2017) did this by translating a source sentence into a linearized, lexicalized constituency tree with the help of seq2tree encoder-decoder architecture based on the work of Vinyals et al. (2015). They reported improvement on the BLEU scores compared with the syntax-agnostic systems on WMT16 German-English dataset and demonstrated that a syntax-aware model performed more reordering of the sentences therefore resolving a different word order problem.

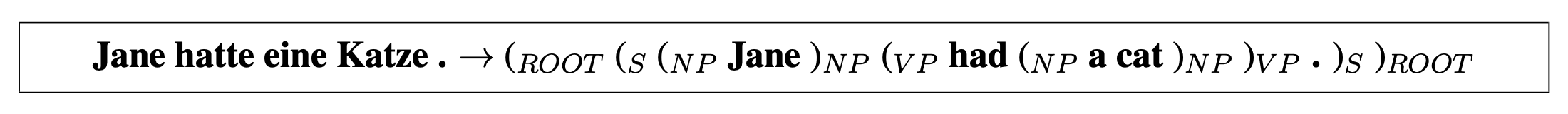

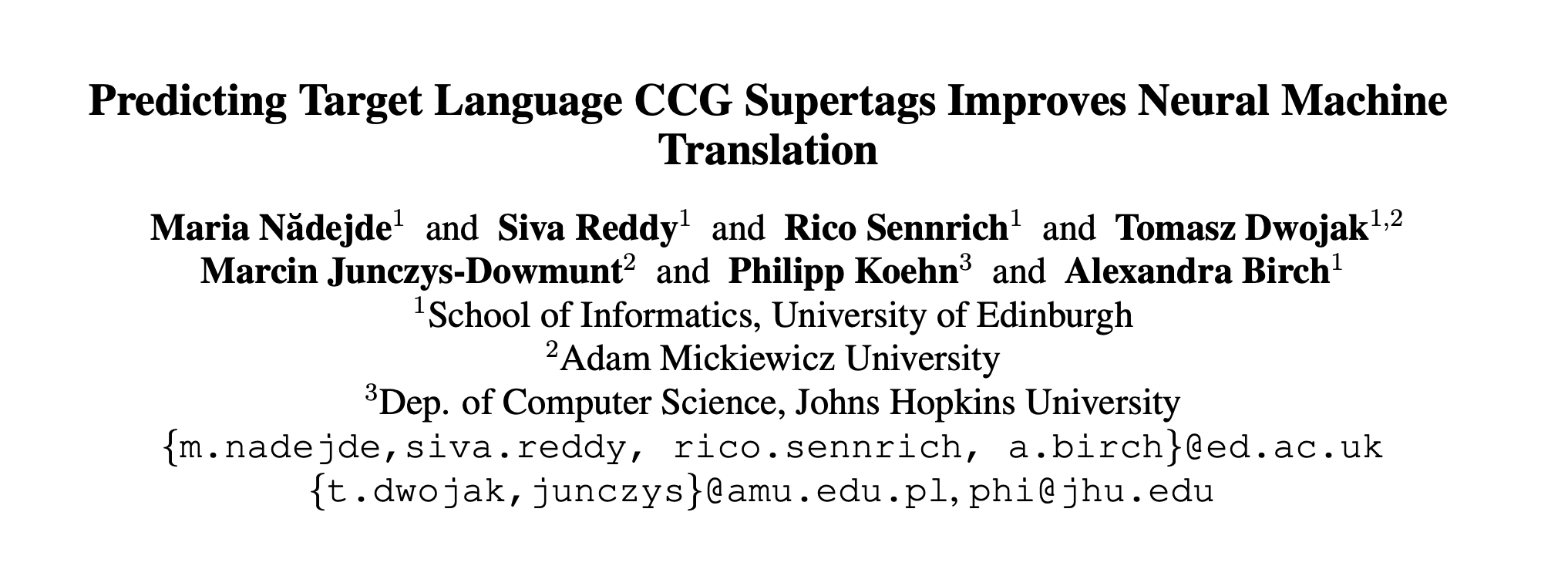

Nădejde et al. (2017) added the syntactic information to the target by including Combinatorial Categorial Grammar (CCG) supertags in the decoder and interleaving them with the word sequence. Unlike factors, where the syntactic information was input (or output) alongside basic words in streams, interleaving supposes that the CCG tags are included as an extra token before each word of the target sequence. This approach showed statistically significant improvement in translation quality for a high-resource (German->English) and a low-resource (Romanian->English) pair as well as resolved some specific syntactic phenomena, e.g. prepositional phrase attachment.

Li et al. (2017) linearized a phrase parse tree into a structural label sequence on the source side and incorporated it into the encoder in 3 different ways: 1) Parallel RNN encoder that learns word and label annotation vectors parallelly, 2) Hierarchical RNN encoder that learns word and label annotation vectors in a two-level hierarchy, and 3) Mixed RNN encoder that stitchingly learns word and label annotation vectors over sequences where words and labels are mixed. Evaluating the effectiveness of different approaches on Chinese-to-English translation the authors demonstrated that Mixed RNN Encoder best improved over the baseline; this model also was better in correcting word alignment and phrase alignment as well as overtranslation (repeating the translated word when the model does not know how to translate the next one) errors.

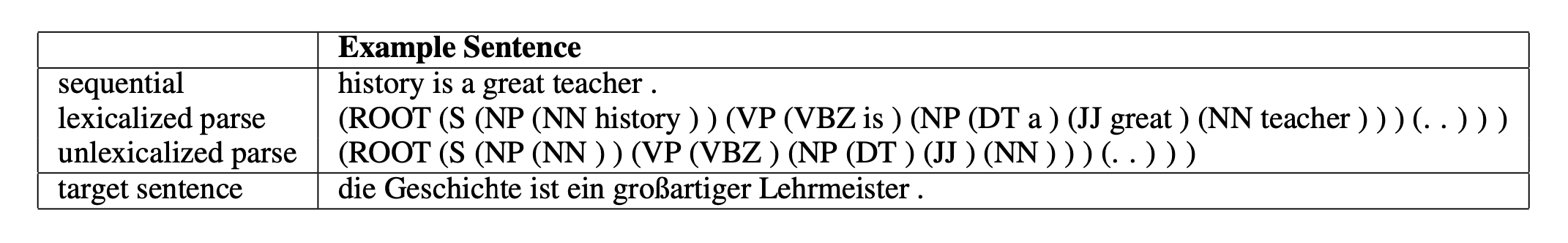

Currey and Heafield (2018) extended the approach of Li et al. (2017) by adapting a multi-source method for incorporating linearized source parses into NMT. This model consisted of two identical RNN encoders with no shared parameters, as well as a standard RNN decoder. For each target sentence, two versions of the source sentence were used: the standard sequence of words and the linearized parse (lexicalized or unlexicalized). Each of these was encoded simultaneously using the encoders; the encodings were then combined using the hierarchical attention combination and input to the decoder. The hierarchical attention combination proposed by Libovickỳ and Helcl (2017) included a separate attention mechanism for each encoder; these were then combined using an additional attention mechanism over the two separate context vectors. The proposed model improved over both seq2seq and parsed baselines on the WMT17 English->German task. Analysis of the performance on the longer sentences also reported an improvement.

So far the factored models only used the morphological and syntactic linguistic information as input (or output) for factored NMT models. España-Bonet and Genabith, 2018 proposed to use the power of semantic networks and semantic information. Using BabelNet (Navigli and Ponzetto, 2012) and its multilingual synsets they built a multilingual NMT system for several European languages where the input sequences were tagged with the word synsets from the BabelNet.

The main characteristic of the BabelNet is that its synsets (the groupings of synonymous words or near-synonyms that express the same concept) are shared between languages. The authors suggested that tagging the sentences in different languages with the same synsets provides us with a sort of semantic interlingua (the words are different but the meaning is the same for content open class words - nouns, adjectives, adverbs, and verbs). It would improve the quality of translation due to sharing the additional source of information from multiple languages but most of all improve the translation for the low-resourced languages by reducing the unknown tokens in the results as well as allow for a translation from the languages unseen by the model (beyond-zero-shot translation).

The authors used the same architecture as Sennrich and Haddow (2016a), concatenating the embedding matrices for factors for the RNN encoder hidden state computation. As they were able to tag only 27% of the corpus with synsets, in the case where the retrieval of the synset was not possible a coarse POS tag was used for the remaining tokens. BPE subword segmentation was also applied.

Using a TED Multilingual corpus of En–De–Nl–Ro–It the authors showed a modest improvement in BLEU and METEOR over the baseline on the other languages to the English translations. The best results were achieved, however, on the previously unseen languages (Spanish and French) where using the synsets along the words showed a double or triple improvement on BLEU and METEOR for translations to English.

Improvements in translation quality for the described architectures against the comparable baselines were usually relatively modest. At the same time, including linguistic information in the encoder-decoder architecture in different ways could often resolve specific problems of translation between languages with richer morphology or significantly different syntax organization (e.g., Chinese and English, German and English, English and French). Some of the problems where the models demonstrated a significantly better performance include the presence of unknown tokens in translations, translations between different word order languages, polysemy in a source language, translation of longer sentences, alignment errors in targets, low-resource and zero-shot translation, and others. Syntactic and semantic information were both shown to be beneficial for NMT.

In the recent works (Armengol-Estapé et al., 2020; Casas et al., 2021) the factored NMT was extended to Transformer architectures and demonstrated good results for improving the low-resource translation. Indeed, we believe that incorporating linguistic information in the current state-of-the-art models will continue to be a promising way of ongoing research.

-

Aharoni, R., & Goldberg, Y. (2017). Towards String-To-Tree Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers) (pp. 132–140). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Armengol-Estapé, J., Costa-Jussà, M. R., & Escolano, C. (2020). Enriching the Transformer with Linguistic and Semantic Factors for Low-Resource Machine Translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.08053.

-

Bahdanau, D., and Cho, K., & Bengio, Y. (2015). Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. In 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, Conference Track Proceedings.

-

Burlot, F., García-Martínez, M., Barrault, L., Bougares, F., & Yvon, F. (2017). Word Representations in Factored Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the Second Conference on Machine Translation (pp. 20–31). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Casas, N., Fonollosa, J. A., & Costa-jussà, M. R. (2021). Sparsely Factored Neural Machine Translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.08934.

-

Currey, A., & Heafield, K. (2018). Multi-Source Syntactic Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 2961–2966). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

España-Bonet, C., & Van Genabith, J. (2018). Multilingual Semantic Networks for Data-driven Interlingua Seq2Seq Systems. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018). European Language Resources Association (ELRA).

-

Garcia-Martinez, M., Aransa, W., Bougares, F., & Barrault, L. (2020). Addressing data sparsity for neural machine translation between morphologically rich languages. Machine Translation, 1-20.

-

García-Martínez, M., Barrault, L., & Bougares, F. (2016). Factored neural machine translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.04621.

-

Koehn, P., & Hoang, H. (2007). Factored Translation Models. In Proceedings of the 2007 Joint Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and Computational Natural Language Learning (EMNLP-CoNLL) (pp. 868–876). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Li, J., Xiong, D., Tu, Z., Zhu, M., Zhang, M., & Zhou, G. (2017). Modeling Source Syntax for Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (pp. 688–697). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Libovickỳ, J., & Helcl, J. (2017). Attention Strategies for Multi-Source Sequence-to-Sequence Learning. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers) (pp. 196–202). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Nădejde, M., Reddy, S., Sennrich, R., Dwojak, T., Junczys-Dowmunt, M., Koehn, P., & Birch, A. (2017). Predicting Target Language CCG Supertags Improves Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the Second Conference on Machine Translation (pp. 68–79). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Navigli, R., & Ponzetto, S. P. (2012). BabelNet: The automatic construction, evaluation and application of a wide-coverage multilingual semantic network. Artificial intelligence, 193, 217-250.

-

Sennrich, R., & Haddow, B. (2016a). Linguistic Input Features Improve Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the First Conference on Machine Translation: Volume 1, Research Papers (pp. 83–91). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Sennrich, R., Haddow, B., & Birch, A. (2016b). Neural Machine Translation of Rare Words with Subword Units. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (pp. 1715-1725). Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Vinyals, O., Kaiser, L., Koo, T., Petrov, S., Sutskever, I., & Hinton, G. (2015). Grammar as a Foreign Language. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Curran Associates, Inc.

@misc{kharitonova-major-breakthroughs-factorednmt,

author = {Kharitonova, Ksenia},

title = {Major Breakthroughs in... Factored Neural Machine Translation (VI)},

year = {2021},

howpublished = {\url{https://mt.cs.upc.edu/2021/03/15/major-breakthroughs-in-factored-neural-machine-translation-vi/}},

}